THROUGH HER EYES - A Historical Analysis of Symbolism in Transgressive Lesbian Art, Fashion, and Performance

Text by Liv Elniski

In the 1920s, as modernism swept through urban landscapes, a vibrant lesbian subculture began to blossom across Europe and the United States. This movement in the arts coincided with the opening of lesbian bars in major cities, as well as significant changes in women’s fashion.

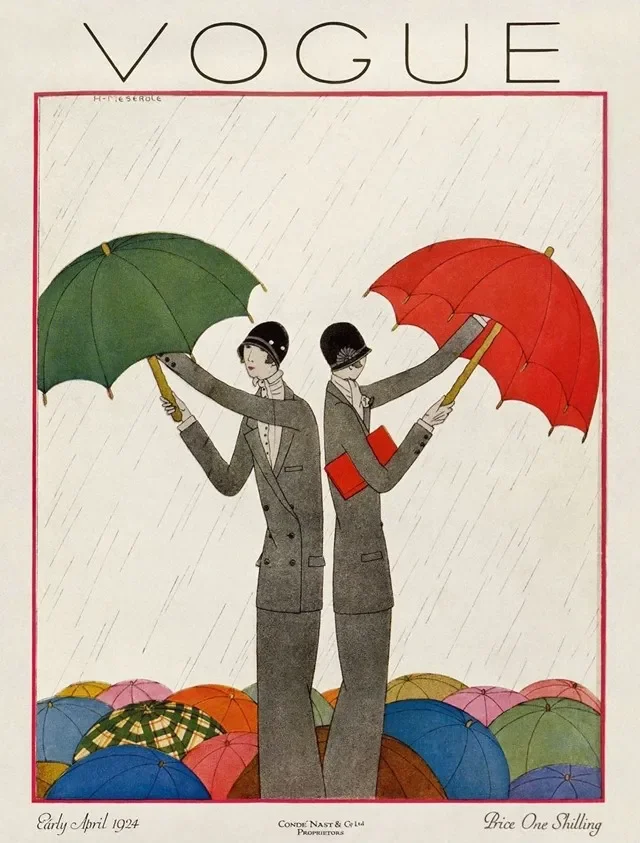

In Europe, visual artists for the first time found themselves on the pages of fashion publications. English lesbian couple Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland, working as Editor and Fashion Editor of British Vogue, platformed a range of queer women artists during their time at the magazine. Many of whom would most likely, in today’s social world, have self-identified as lesbians. This was the first of many decades of Vogue being a dictatorial platform that not only reflected trends in fashion but also in other areas of the arts. This change in the structural integrity of the publication was spearheaded by lesbians and soon became the blueprint for most other culturally relevant magazines.

Regarding this, lesbian fashion historian Eleanor Medhurst muses in her book Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion, “Modernism became almost a code for queerness.” Between the years of 1922 and 1926, the magazine frequently alluded to styles and mores associated with emerging sexual subcultures through both covert and overt, symbols and codes. This not only kept insiders abreast of developments in these communities but encouraged a wider audience of fashionable women to identify with a “modern” openness to new ideas.

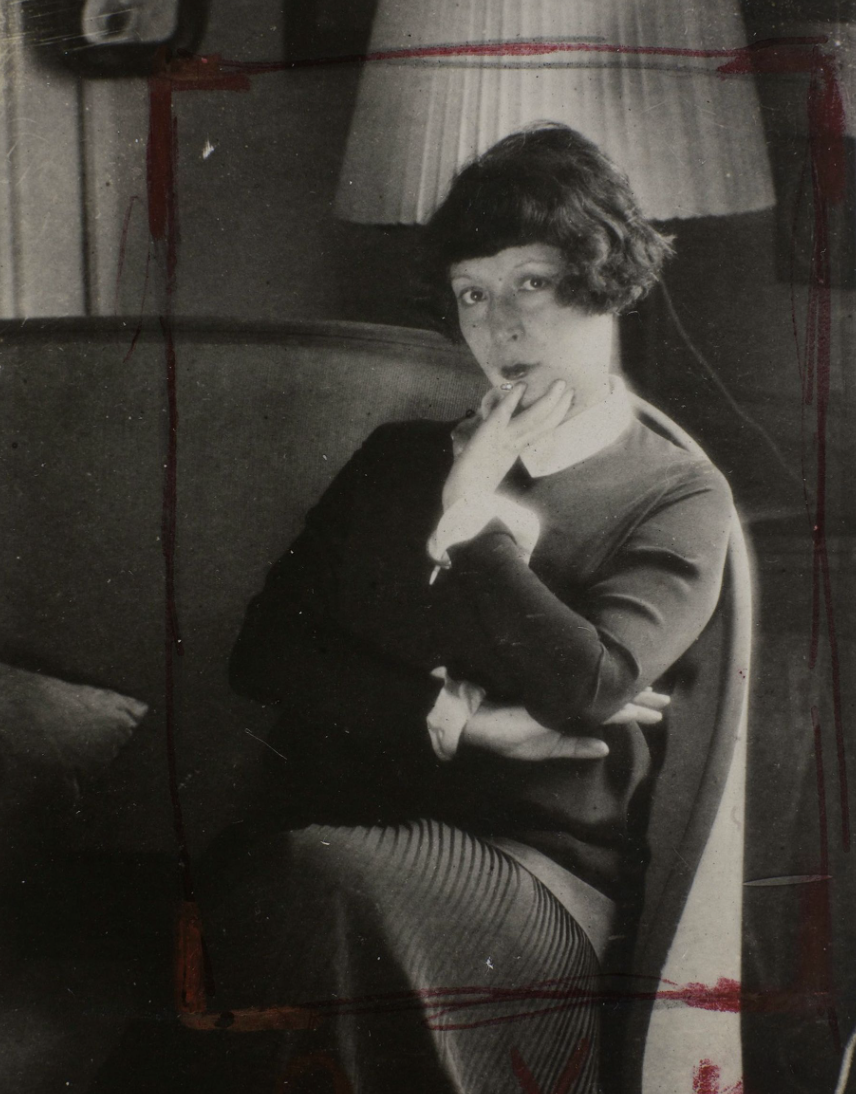

A portrait of Marie Laurencin by Man Ray, 1925, image courtesy of the Barnes Foundation

French-born painter Marie Laurencin was one of many queer women given a voice on the pages of Vogue. A caption under one of Laurencin’s works published in early December 1924 depicts frolicking women and animals. According to Christopher Reed’s 2015 essay “A Vogue That Dare Not Speak its Name: Sexual Subculture During the Editorship of Dorothy Todd, 1922–26” the caption in the magazine notes how within the “new poetic world” of the painter’s mind, there are “slim girls..., horses, dogs, and birds, but never a man.” Laurencin is often recognized for using animals as sapphic symbolism. One of her works entitled “Women with Dove” depicts the painter, alongside couturier Nicole Groult: the pair are reading a book, a white dove perched on the spine. The dove gazing upon the women is said to represent sapphic love as if the intimate, amorous nature of the two was not obvious enough.

In January 1925, British Vogue referred to Laurencin as “the sister of Sappho” (Reed). Although she was never forthcoming with her sexual identity, Laurencin is known to have spent many nights in Parisian lesbian bars such as Le Monocle, and congregating with other known lesbian creatives such as Gertrude Stein. Laurencin’s style during this time reflected radical trends in the fashionable female mode of the day. The “La Garçonne” style, characterized by cropped hair, men’s suiting details, and a queer sensibility, reigned in popularity among young women with an affinity for the avant-garde. Although this style became mainstream among the fashionably literate, it certainly lent itself well to lesbians, many of whom instinctively had a strong preference for masculine styles. According to fashion historian Raissa Bretaña, the name of this look, derived from a novel about a woman with lesbian tendencies, came to define fashions of queer artistic circles of the 1920s.

French photographer Brassai’s images of 1920s queer nightlife chronicles the fashions of women like Laurencin. Le Monocle bar in Montmartre was a place of refuge for Parisians, including struggling artists, bohemians, burlesque dancers, and the city’s vibrant lesbian community. Lesbians and fellow queers safely explored their gender and sexual identities through their sartorial choices within the confines of European nightlife. Notably, the monocle became a popular accessory among queer women, as documented by Brassai’s camera lens. Could this possibly have been a centuries-old way of winking at other lesbians, of flashing your carabiner? Of saying “I’m one of you?” In his images, one can find butches, femmes, trans people, and gender non-conforming individuals congregating under one roof.

Writer Natalie Barney, who lived openly as a lesbian during a time when it was dangerous to be so, was a figurehead in the 1920s Parisian lesbian scene. Famous for only admitting women into her salons, she created a safe space for lesbians, who became the majority in her home. Marie Laurencin and her contemporaries often attended dimly lit evenings hosted by Barney (George Wickes). As well as Laurencin, Ethel Mars, and Maud Hunt Squire were two of the women who frequented Gertrude Stein’s fruitful, artistic haven located at 27 Rue de Fleurus. According to Jule Collins’s essay “Art Is Pride: A Look at the Lives of Maud Hunt Squire and Ethel Mars,” the couple who lived in Paris met as students at Cincinnati Art Academy in the 1890s. They graduated and moved to New York for a short time before relocating to Europe, which at the time was an overwhelmingly common experience for queer Americans. James Baldwin, an American writer and civil rights activist, has spoken about his experience as a Black queer man in America, fleeing to Europe to escape racism and prejudice. It is certainly possible that Mars, Squire, and others alike, made this move for similar reasons.

Maud Hunt Squire and Ethel Mars (right), Springfield, Illinois, c.1898, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC.

The two began their life in Paris in 1906. First-hand accounts of these women, referred to as “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene” by Stein, are difficult to come across. Their lives have been written about and mythologized by just a few, including Medhurst and Collins. Salons such as Stein’s housed intellectuals, artists, and broadly “modern” women, who welcomed the pair—known for being “in favor of flaming orange hair, powder, and rouge, as well as copious amounts of what sounds like kohl, around their eyes,” with open arms. The couple is described as bohemian dressers by Medhurst. Bohemian broadly meaning an unconventional approach to fashion and self-presentation, “one usually flavoured by personal and political ideals.” This unspoken signaling of queer and lesbian identity through unconventional sartorial and beauty choices is a glowing lilac thread in the story of lesbian fashion.

Fashions with queer sensibilities stretched across the Atlantic, with on-screen, sapphic stars including the likes of Louise Brooks, Marlene Dietrich, Eva La Gallienne, and Alla Nazimova. According to Diana McLellan’s book The Girls: Sappho Goes to Hollywood, Nazimova, who could be considered the mother of golden-age Hollywood lesbianism, hosted sex-filled parties at her home colloquially referred to as “the garden of Alla,” filled to the brim with fashionable sapphics. Her garden parties of wonderful ladies were the New York and Hollywood equivalent to Parisian, primarily lesbian, literary salons.

In 1926, lesbian love walked out on a New York stage for the first time, when Edouard Bourdet’s play The Captive debuted at the Empire Theatre on Broadway. Irene, played by Helen Menken, is a lesbian engaged to a man, tortured by her love for Madame d’Aiguines (McLellan). Menken’s face, painted ghastly white, expressed the emotional toll she experiences at the hands of her perverse feelings of desire! Her lover was never actually seen on stage, rather throughout the story she sends her love bundles of violets, the flower that lesbian poet Sappho of Greek antiquity and her lovers wore during happily doting hours on the isle of Lesbos in 7th century B.C.

Queer botany seems to have originated with Sappho, as many visual depictions illustrate her and other women often alongside or holding purple flowers. As indicated by Emma Petits’ poem translated by Mary Barnard, “Sappho: The Origin of Lesbians,” Sappho writes about a lost lover who left her shackled by love, and how she will miss “all the violet tiaras, braided rosebuds, dill and crocus twined around [her] young neck.” Lesbians in Paris around the time of this theater production wore violets pinned to their clothes, possibly as a symbol of affiliation to Sappho and the island of Lesbos. This may have to do with the fact that in 1903, in a contemporary translation of Sappho’s writing, her lover was for the first time interpreted as a woman.

This three-act melodrama caused a major scandal when it opened in New York. The purple on-stage token of flora began a decades-long fashion across the Western world of violets as a symbol of sapphic love. Eva la Gallienne and Mercedes De Acosta, who were together at the time, sat front row of the show time and time again until the queer storyline was eventually deplatformed, being violently described by the press as the “MENACING FUTURE OF THEATER” (McLellan). In April of 1926, New York’s Penal Code of 1909 was amended to bar productions dealing with “sex degeneracy or sex perversion.” And just like that, lesbians had to crawl back to their dimly lit homes to enjoy sapphic art in private.

Subtle tie signs within sexual subcultures in the lesbian community have persisted, despite there being less of a societal need to use covert signals over time. Images like that of Brassai’s, Vogue archives, paintings done by Laurencin as well as her contemporaries, and work by writers like Sappho and Stein all aid in immortalizing lesbian identities from a full century ago all the way to antiquity. Access to these works ensures the existence of identities that have historically been hidden and voices that have been silenced.